Artificial respirators are the main means of keeping patients hard hit by Covid-19 alive. Let's go back to the genesis of intensive care.

In 1952, Copenhagen (Denmark) was the epicenter of one of the worst polio epidemics of all history. That year more than 5,700 cases were registered in the city, of which 2,450 showed signs of respiratory paralysis. The only hospital in the region authorized to treat the disease – the Blegdam – was taken by storm, registering between 30 and 50 new patients a day during the first weeks after the onset of the crisis.

The city's doctors and nurses were unfortunately not equipped to deal with such an influx of patients. They only had one iron lung which at the time was the primary means of treating patients with respiratory failure.

An iron lung, roughly, is a kind of large cylindrical drum in which the body of a patient is positioned (the head and neck remain in the open air). Pumps periodically increase and decrease the pressure inside the compartment. When the pressure drops below that of the lungs, outside air is drawn in through the upper airways to fill the lungs. And conversely, when it rises above that of the lungs, the air is expelled from the lungs.

The oscillation of intrathoracic pressure thus allowed the inspiration and expiration of air into the lungs. The method was effective; thousands of lives were saved around the world in the middle of the 20th century thanks to this box. But for Blegdam Hospital, that was not enough.

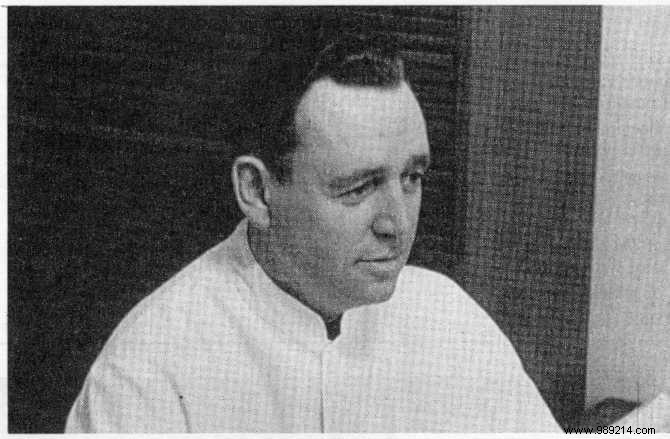

Desperate to find a solution to deal with the influx of patients, the hospital's chief medical officer called a meeting attended by a young anesthetist, named Bjørn Ibsen. The latter, who had just returned from a training course at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, in the United States, had the intuition that the patients affected by the epidemic did not die of viral overproduction in the blood or the brain, as suggested, but due to an increased CO2 content in the blood following hypoventilation.

His hunch was later confirmed by autopsies of four dead polio patients, ventilated by iron lung, who indeed had excessive levels of carbon dioxide despite their lungs being perfectly operational. He then proposed the idea of relying on an opposite approach:that of continuous positive pressure ventilation .

In other words, the young anesthesiologist suggested to blow air directly into the lungs of the patients to expand them, then allow the body to passively relax and exhale.

To do this, he proposed the use of a tracheostomy , which involves making a small incision in the neck and then passing a tube through the trachea to deliver oxygen to the lungs. His idea was welcomed, and the next day, August 26, 1952, he was allowed to test his technique.

The first patient to take advantage of this was a 12-year-old girl named Vivi Ebert, whose respiratory muscles were already partially paralyzed. As a result, she had a lung clogged with phlegm, and threatened to suffocate with her own saliva in the short term. The doctor then aspirated the pulmonary mucus of the young girl placed under general anesthesia and took a ventilator in order to carry out the manual ventilation of the patient. As expected, after a few minutes young Vivi was ventilated and her lungs were free of saliva.

Following this demonstration, it was therefore decided to operate in the same way with all the other patients in respiratory distress in the hospital. Except that at the time, there were no fans. Thus, more than 250 medical students and 260 nurses were urgently recruited to provide manual breathing for the patients concerned. Several teams were formed, taking turns every six hours. This remarkable operation lasted several weeks and, thanks to these efforts, the mortality rate for patients fell from 87% to around 25%.

A few months later, a child with tetanus was admitted to the hospital in Blegdam. Bjørn Ibsen, considering that the symptoms of patients with tetanus and patients with poliomyelitis were technically very similar, decided to operate in the same way.He thus ventilated the child for a period of 17 days , until he wakes up. But the bill had ultimately cost the hospital dearly. This is why the city of Copenhagen commissioned the young doctor to create an anesthesia department which he would direct as an intern.

Bjørn Ibsen headed this department from 1954 and equipped a monitoring and ventilation room along the way. Thus, the concept of an intensive care unit (ICU) was born . Subsequently these units proliferated in the rest of the world and the use of positive pressure, with ventilators, became the norm.

Source