Research from the University of Oxford highlights that the technology behind the Oxford-AstraZeneca Covid-19 vaccine, combined with an immunotherapy approach, could help fight cancer.

Although the cancer mortality rate has been constantly decreasing for 25 years, in particular thanks to the improvement of treatments and diagnostic methods, these diseases still cause many victims each year (more than 157,000 in France in 2018). Also, work is continuing around the world to identify one or more approaches to prevent or cure cancer. Some laboratories are focusing on the development of a vaccine. And there is progress.

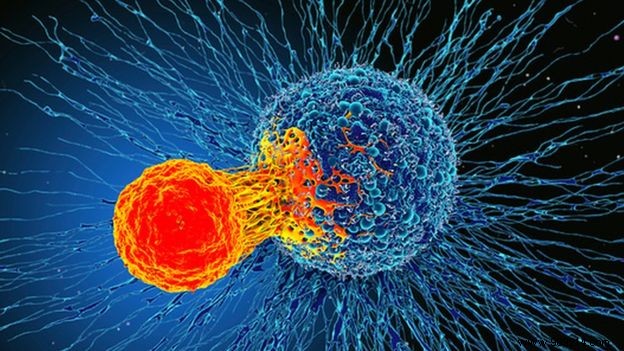

Recently, researchers at the University of Oxford developed a vaccine approach combined with immunotherapy. In tests in mice, the vaccine boosted levels of anti-tumor immune cells, while immunotherapy made them more effective.

Recent advances in immunotherapy have led to unprecedented improvements in outcomes for patients with advanced cancers, particularly through therapies targeting immune checkpoints ( ICB). These are ligand-receptor interactions that negatively regulate effector T cell function. Inhibition of these control pathways with monoclonal antibodies can enhance the priming of anti-tumor T cells and thus restore their activity.

However, many patients do not respond to this type of treatment due to a lack of pre-existing antitumor cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs). Here, the Oxford team has developed a therapeutic vaccine to precisely increase the levels of these cells in the body.

The serum, which relies on one of the same viral vectors used in the Oxford-AstraZeneca Covid-19 vaccine, was specifically aimed at increasing cell levels TCD8+. These are primed to target two proteins called MAGE-A3 and NY-ESO-1, which only appear on the surface of cancer cells.

In tests in mice, the vaccine actually increased levels of these cells, while immunotherapy allowed them to target tumors more aggressively. Together, these two approaches significantly reduced tumor size and improved subject survival compared to control mice or immunotherapy alone. Half of the mice in the test group were still alive after fifty days, while none of the mice in the control group survived longer than thirty days.

“Our cancer vaccines elicit strong CD8+ T cell responses that infiltrate tumors and show great potential to improve the efficacy of cancer blocking therapy. Immune Checkpoints and Improve Outcomes for Cancer Patients” , confirms Adrian Hill, co-author of the study.

With these results validated, the Oxford researchers are now planning a first phase 1/2a clinical trial. Offered to 80 patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), it should begin at the end of the year.