There has been so little flu transmission during the COVID-19 pandemic that some of its viruses may have disappeared. If so, the lower diversity of these pathogens could facilitate the development of more targeted vaccines.

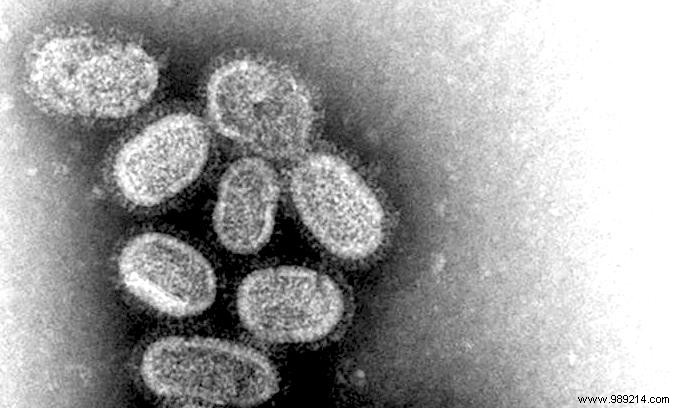

Influenza is an infectious disease caused by certain RNA viruses of the Orthomyxoviridae family. It is seasonal, occurring mainly during the autumn-winter period in temperate countries. The number of victims varies from 290,000 to about 650,000 each year worldwide.

However, as expected, flu cases have dropped dramatically in recent months. A phenomenon, note the experts, that we owe mainly to the wearing of a mask and other "barrier measures" put in place in many countries to fight against the Covid-19 pandemic.

In fact, two strains of these RNA viruses have visibly disappeared from the radar for a year, reports STAT magazine.

To explain which influenza viruses might have disappeared, it is useful to go back to their classification. Two families of influenza viruses cause seasonal influenza in humans:influenza A and influenza B. Influenza A viruses are divided into "subtypes" based on two surface proteins known as hemagglutinin (H ) and neuraminidase (N).

Currently, the H1N1 and H3N2 subtypes are the ones that stand out in humans. Finally, within these two subtypes are subclassifications, or clades, with H3N2 viruses having more diversity than H1N1.

Influenza B viruses, on the other hand, have no subtypes but are divided into two lineages known as B/Yamagata and B/Victoria.

What STAT tells us today is that the H3N2 subtype, known as 3c3.A, and the B/Yamagata lineage would not officially have not detected since March 2020 .

“I think there's a good chance he's gone. But the world is wide” , emphasizes Trevor Bedford, of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, referring to H3N2.

"Just because no one saw it doesn't mean it's gone, does it? But actually, he could see disappeared” , adds Florian Krammer, of the Icahn School of Medicine Mount Sinai in New York, this time referring to the B/Yamagata lineage.

Richard Webby, in charge of studies on the ecology of influenza in animals and birds at the WHO, thinks for his part that there has indeed been a large reduction of the diversity of these viruses in circulation, but that they have not completely disappeared.

It is therefore still unclear whether these two forms of virus have really disappeared. But if so, health authorities might have an easier time targeting the strains in vaccine development.

Indeed, the reason we continue to suffer from the flu every year is because the virus keeps mutating to evade our immune defences. H3N2 viruses, in particular, constitute a particularly diverse group.

In order to produce an annual vaccine, epidemiologists then target the few strains that seem to be the most prevalent from one year to the next. Of course, a universal vaccine capable of protecting us for several years would be ideal. But for now, it is not yet available.