Brain oxygen levels of elite freedivers may drop even lower than that of seals on their deepest dives, new research suggests .

Elite human freedivers perform some of the most exceptional feats of human endurance, in what is one of the most extreme sports in the world. Doing dives lasting over four minutes and reaching depths of over 100m in a single breath hold, freedivers push the limits of what the human body can tolerate. But what is really going on in the bodies of these athletes?

Until now, understanding the effects on the brain and cardiovascular system of these exceptional dives has been difficult, as all research has been done during simulated dives in the laboratory.

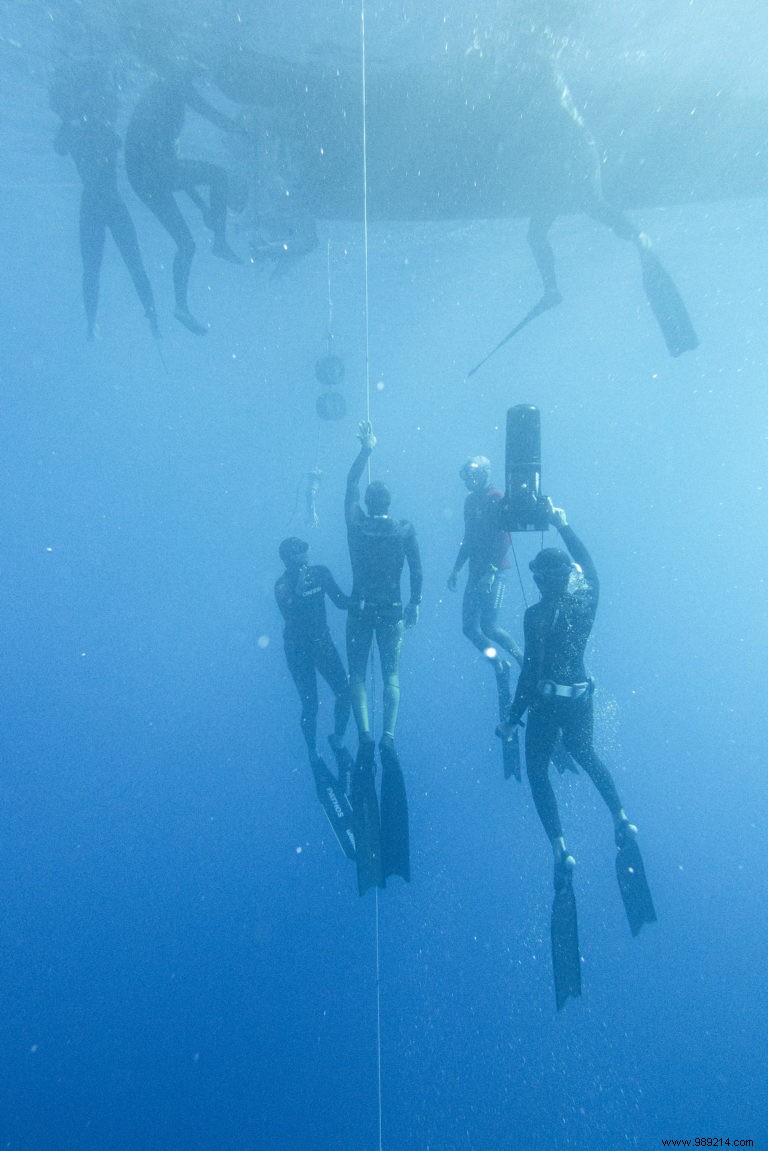

As part of a recent study published in the journal Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B , an international research team has developed a device capable of measuring the heart rate, blood volume and oxygen levels in the brains of freedivers while withstanding the extreme ocean pressures experienced at depths of more than 100 meters.

The device works similar to a smartwatch – using light-emitting LEDs in contact with the skin.

For this work, the team collaborated with professional freedivers on the high seas. And the results are dizzying. Blood oxygenation levels, normally pegged at around 98%, have indeed dropped to 25% about 107 meters deep! This is better than in seals, notes the statement from the University of St Andrews. For comparison, a "typical person" would normally lose consciousnessunder 50% oxygenation .

Obviously, these divers cannot compete over time. Seals can hold their breath for about two hours.

During the dives, the researchers also measured heart rates as low as eleven beats per minute , for the one and only purpose of helping to preserve those oxygen levels. Again, the heart rate of these divers was as low as that of seals or some whales.

“ Beyond physiological responses exceptionalities that freedivers exhibit and the extremes that they can tolerate, they can be a very informative physiological group ” , explains Chris McKnight, of the University of St Andrews and co-author of the study. “ Their physiological responses indeed provide a unique way to understand how the body responds to low blood oxygen, low brain oxygenation, and severe cardiovascular suppression ” .