Danish researchers have identified a familiar survival technique developed by some cancer cells that involves repairing their membrane and "digesting" the damaged parts. By inhibiting this process, we could prevent their evolution and proliferation.

Cancer cells develop all sorts of tricks to thrive in the human body. Last January, a study published in the journal Cell revealed that these cells were able to enter a "dormant state" to avoid destruction by chemotherapy. This could explain why some people respond poorly to these treatments, but also why some cancers seem to "come back" suddenly after several years.

More recently, a team from the University of Copenhagen discovered that breast cancer cells can also rely on the process of macropinocytosis in order to repair their damaged membrane. This work is published in the journal Science.

The plasma membrane shapes and protects the eukaryotic cell from its environment. Sometimes these membranes suffer some damage, which can lead to cell death. In response, one of the techniques the cells use is macropinocytosis, which involves covering the damaged area with a section of intact membrane, sealing the hole in seconds. The damaged section of the membrane is then broken down into small spheres transmitted to the cell's lysosomes responsible for breaking them down.

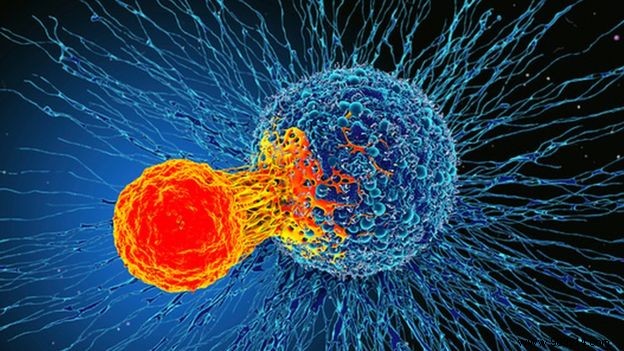

These repair mechanisms have recently been observed in cancer cells for the first time . The researchers made the discovery after bombarding breast cancer cells in the lab with a laser to punch tiny holes in their membranes. The team found that these "attacks" triggered macropinocytosis. They also discovered that they could interfere with the process of breaking down damaged membranes, ultimately preventing their digestion and promoting cell death.

“Our research provides very basic insights into how cancer cells can survive “, explains Jesper Nylandsted, main author of this work. “In our experiments, we have also shown that cancer cells die if the process is inhibited . This points to macropinocytosis as a target for future treatment “.

Researchers will continue to work to study these mechanisms of cellular repair. For Stine Lauritzen Sønder, co-author of the study, it will also be interesting to see what happens after the membrane closes. "We believe the 'first patch' is a bit rough and further repair of the membrane is required afterwards. This may be another weak point that we want to take a closer look at “.